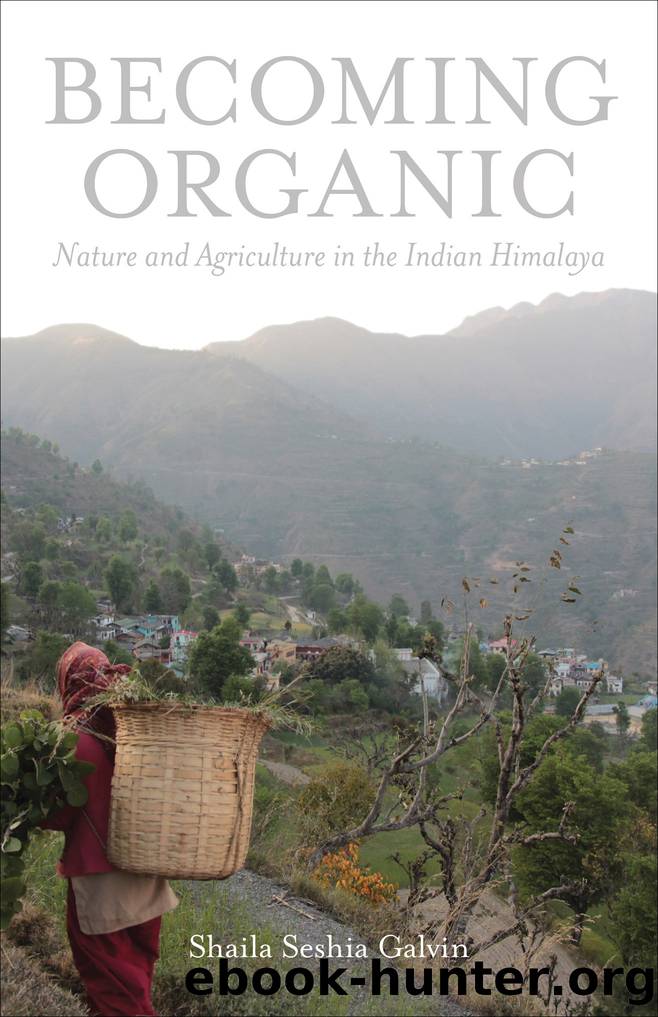

Becoming Organic: Nature and Agriculture in the Indian Himalaya by Shaila Seshia Galvin

Author:Shaila Seshia Galvin

Language: eng

Format: epub

Publisher: Yale University Press

Published: 2021-05-15T00:00:00+00:00

Cultivating Demand

Over the course of my time at the UOCB, efforts to create market linkagesâand indeed markets themselvesâtook varied forms, including selling organic products in melas and exhibitions, which I discuss in chapter 5, as well as buyer-seller meets on a range of scales, from small-group discussions on the margins of cultivated fields to organized meetings in larger venues. The UOCB stood between Uttarakhandâs hill farmers, who cultivate crops little known in urban markets, on the one hand, and a still-inchoate world of existing and prospective buyers, markets, and consumers, on the other. One day, Deepa Agarwal departed from the bureaucratized language of âfacilitationâ to describe the UOCB more powerfully and evocatively as an âumbilical cordâ for the regionâs hill farmersâa conduit of technical and institutional nourishment that would in time enable them, in her words, to âstand on their own feet.â

She was not alone in her conviction that the UOCBâs work was to grow markets and organic farmers together. In late 2007, Ajay Solanki, the marketing manager of COF, told me that they began with âa base of products that had never before been seen in marketsâ in Delhi and other metropolitan areas. These products included finger millet, barnyard millet, black soybeans, and other coarse grains, pulses, and dryland rice. Of the forty-odd organic commodities on their product list, he observed, only tenâamong them spices, kidney beans, cereals, wheat, and vegetablesâhad reasonable demand in the market. The challenge for the marketing cell was to discern where there was demand and organize for its supply, an approach that Ajay described as consumer-driven. Though this had been accomplished in the Doon Valley for basmati and, more recently, wheat, it has proved more difficult in the hills, where production is more geographically diffuse and the diversity of crops and varieties is higher. In this circumstance, the UOCB sought to identify niche markets for spices such as chili, turmeric, and ginger as well as certain kinds of pulses and coarse grains. For example, the UOCB has worked to cultivate a market for paharÄ« toor in Delhi, as toor (pigeon pea) is a pulse widely used in regional cuisines across India.

Demand for other hill crops does not exist simply because such crops are not widely consumed outside the region or in urban centers. The UOCB has struggled to find a market for finger millet, for instance. With high calcium and iron content, this crop is produced mainly for subsistence. Indeed, in conversations with urban and suburban residents, I encountered the perception that the dark color of the flour produced from finger millet, which is often consumed as roti (a type of flatbread common in many regions of north India), would make oneâs complexion âblack,â something that many considered undesirable in a cultural milieu that privileges fair skin.17 Wheat, rice, and maize were therefore preferred cereal crops. When I arrived in 2007, the UOCB had already undertaken a series of efforts to find buyers for this widely cultivated coarse grain. These included an agreement with

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Automotive | Engineering |

| Transportation |

Whiskies Galore by Ian Buxton(41984)

Introduction to Aircraft Design (Cambridge Aerospace Series) by John P. Fielding(33113)

Small Unmanned Fixed-wing Aircraft Design by Andrew J. Keane Andras Sobester James P. Scanlan & András Sóbester & James P. Scanlan(32788)

Craft Beer for the Homebrewer by Michael Agnew(18230)

Turbulence by E. J. Noyes(8039)

The Complete Stick Figure Physics Tutorials by Allen Sarah(7361)

Kaplan MCAT General Chemistry Review by Kaplan(6922)

The Thirst by Nesbo Jo(6921)

Bad Blood by John Carreyrou(6610)

Modelling of Convective Heat and Mass Transfer in Rotating Flows by Igor V. Shevchuk(6431)

Learning SQL by Alan Beaulieu(6274)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6261)

Man-made Catastrophes and Risk Information Concealment by Dmitry Chernov & Didier Sornette(6001)

Digital Minimalism by Cal Newport;(5746)

Life 3.0: Being Human in the Age of Artificial Intelligence by Tegmark Max(5541)

iGen by Jean M. Twenge(5406)

Secrets of Antigravity Propulsion: Tesla, UFOs, and Classified Aerospace Technology by Ph.D. Paul A. Laviolette(5364)

Design of Trajectory Optimization Approach for Space Maneuver Vehicle Skip Entry Problems by Runqi Chai & Al Savvaris & Antonios Tsourdos & Senchun Chai(5062)

Pale Blue Dot by Carl Sagan(4994)